Engaging learners through questions is a pretty common practice. In fact, it may likely be one of the pedagogical approaches most often used for the last 100+ years. Between 300-400 questions are asked a day in an average classroom according to a study from the University of Waterloo, which makes up a substantial percentage of classroom time. Now, as education slowly transitions from only ever giving end-of-year summative assessments to more ongoing formative assessments, you might think this is good news given how often questions are asked during a typical lesson. Unfortunately, there is more to unpack in this story.

At the annual International Association for Education Assessment (IAEA) conference in Fall 2022, various main directions for assessment practice were shared. One of those themes is the general shift from summative to formative assessments, which we’ll dive into here The pandemic undoubtedly helped to speed this process as systems across the world chose to do away with their end-of-year high-stakes assessments in favor of more ongoing reflections of students' progress, and have remained that way even with learning returning to ‘normal’.

If you are new to the world of assessment, a great analogy to understand the difference is to think of a cook preparing a meal at a restaurant. What the customer tastes could be considered a summative assessment while what the cook tastes as they prepare the meal would be considered formative – the cook might add salt or other spices along the way before the meal is complete. Similarly, formative assessments should help inform and guide the next steps in a learner's journey. Understanding this concept helps unpack why simply asking more questions during a learning interaction does not necessarily mean that active learning is taking place.

As early as 1912 studies found that teachers spent as much as 80% of classroom time asking questions and when the same study was repeated in the 1980s not much had changed.

Today, with the use of tech tools, researchers are tracking teacher-learner classroom interactions and we see much of the same as we did in the early 1900s. In most classrooms, most questions are asked by the teacher. And the majority of those are fairly simple, ‘low-level’ cognitive questions that only work to engage a handful of students with basic memory recall. They’re often not getting at deeper student understanding of concepts. Simply put, although students everywhere get asked a lot of questions every single day, these questions aren’t helping them learn more, or better.

Challenges of Formative Assessment

To better understand why this happens, let’s unpack the challenges of formative assessment and look at some ideas for solving them:

Mindsets:

- Shifting from grade-based to authentic and continuous assessments

- Assumptions that verbal questions responded to by a few represent the progress of the entire class

System:

- Policies that govern teaching and learning

- How does the structure enable learning engagement, feedback, and active participation?

- Tension between assessing vs improving

Teachers:

- Lack of clarity surrounding strategies and implementation

- Not often used for constructive feedback, learners support and guide student behavior

- Results are not often discussed with colleagues in order to share individual and collective insights

- Unclear how to include assessment with existing tools or workflows

- Lack of time, flexibility

Students:

- Understanding how to use the info they learn about themselves and their learning

- Integrating their participation and ideas

Among the strategies to address these challenges, it is important to look at how pre-service and in-service education is used to address mindsets and teacher knowledge and practice. Policies need to promote continuous feedback and elevate the value of involving students in the process of feedback. Building the right culture throughout the school community can also help reinforce formative assessment as a driver of learning and support teachers in their intentional planning and peer sharing.

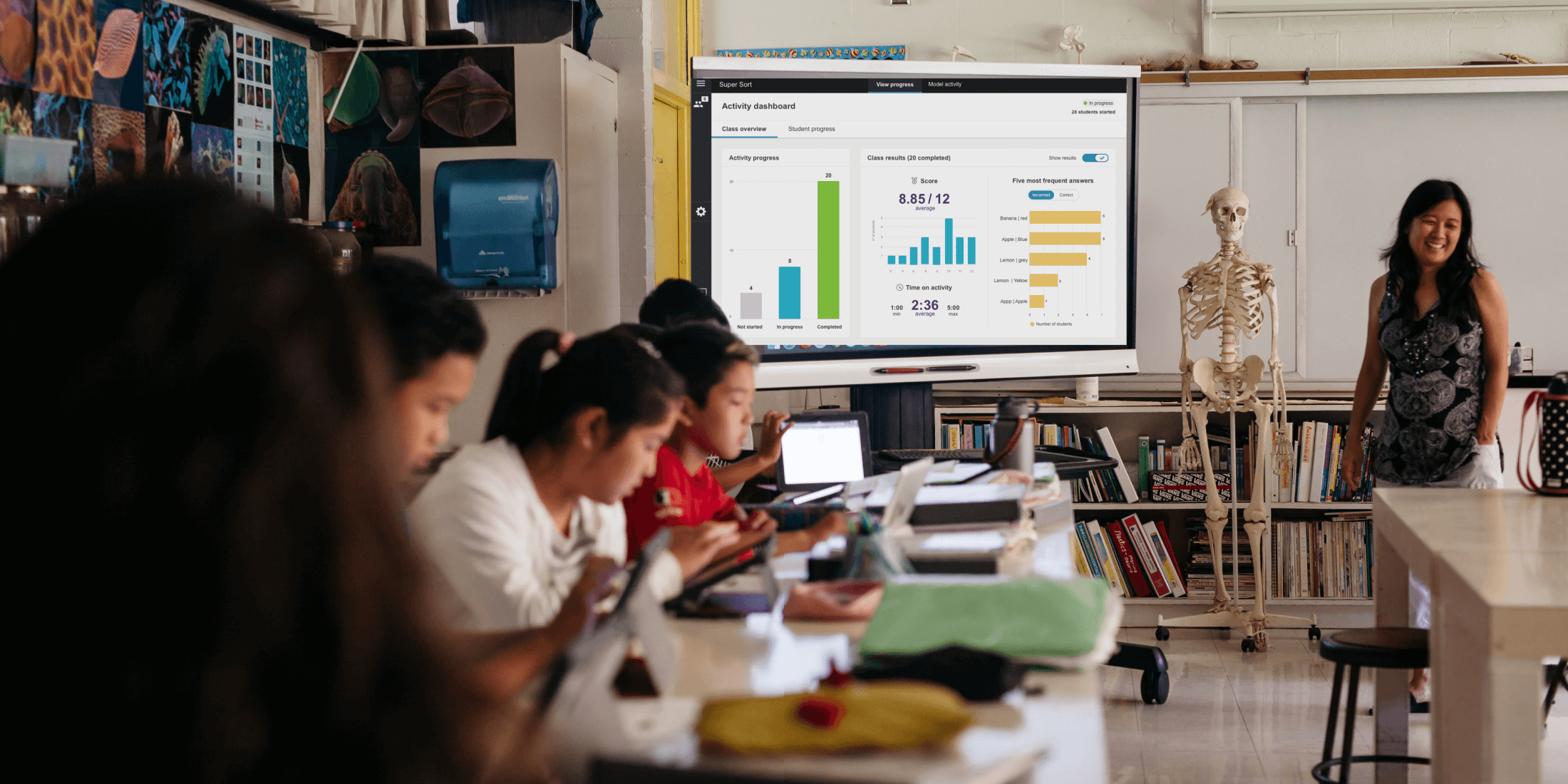

Promoting the use of digital tools to ease planning and orchestration, and ensuring all learners are involved in the process is now made even easier than ever before especially with free-to-use online tools like Lumio.

The pandemic has helped ensure classrooms are more connected digitally than ever before. Classrooms should be looking to leverage digital tools as part of their planning and delivery of formative assessments. The good news is that we can leverage the already existing behaviors of asking questions in class to make small tweaks and get more from those questions. The process of using free, digital, easy-to-use tools to better plan when and what questions get asked also instantly helps ensure teachers get visibility into all learners’ progress. It also provides opportunities for learners to reflect on their learning journey. And, perhaps most importantly, it creates a rich reflective piece for teachers to begin having discussions with their peers.

It’s these small, micro changes to our existing practices that have the potential to powerfully guide students and teachers along a learning journey and into active learning experiences where all learners thrive.

References:

Leven, T. and Long, R. (1981). Effective instruction. Washington DC: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.)